Spring 2001

Mapping Reflects Real Life, Real People

By Kamrhan Farwell

Assistant Metro Editor

The Press-Enterprise, Riverside, CA

I call it fast-food journalism. Make two calls, snag an expert, skim the best from the Internet and grab a token “real person” to make it seem like home cooking.

Bing, bang, bong.

And that burger’s done, just like the 30 million before it.

We don’t always do stories this way, but too often we do. Many newspaper stories come across as bland, unimaginative and preconceived. Worse yet, irrelevant to the lives of our readers.

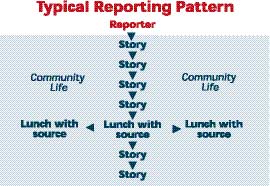

Our job is to reflect real life, real struggles and real people. But where do we go? We look in places where news is found reliably – City Council meetings, boardrooms, phone calls and lunch with people who hold big titles. But these are narrow portals for information to flow from the world to our pages.

The Press-Enterprise and many other newspapers around the country are trying to broaden the scope using a strategy called “civic mapping.” The idea is to return agenda making to the people in our communities. If we listen hard enough in the right places, they will tell us what really matters.

An Experiment

The Press-Enterprise is a medium-sized daily paper with nine zoned editions. We cover more than 30 cities and all the county areas in between.

We were looking for a way to improve our coverage and protect our turf in a competitive market. We also were seeking more lively, interesting story ideas.

Other newspapers in San Diego, Orange County, Virginia and Tacoma touted successful runs at civic mapping. The Press-Enterprise decided to try a little experiment.

Ours was not a fancy plan. No funding, extra people, money or time. One bureau would try out the concept to see if it should spread to other offices.

I supervised the Moreno Valley bureau when it became the guinea pig. We created our plan based on a few conversations with civic mapping pioneers and on a booklet called “Tapping Civic Life,” prepared by the Pew Center for Civic Journalism and media consultant Richard Harwood.

Now, civic mapping is making its way through every bureau at The Press-Enterprise. News managers liked what they saw, skeptical reporters found a new tool and readers noticed a difference.

The Method

The map itself – which is not a geographic map – is not the point of all this, but a by-product of a process.

We began by forming three teams made up of reporters, editors, photographers, news assistants, sports people, business and lifestyle staffers.

We chose three areas of focus in Moreno Valley: A low-income neighborhood, a gated housing tract and the local youth sports community.

We started with the “civic leaders” of each community – the folks we already talk to all the time. This group included City Council members, well-known activists, Little League board members and the director of the Parks and Recreation Department.

Instead of calling on these people to answer questions for a story, we asked them to help us understand their community.

Team members met with these people and simply asked them to talk about their group. We asked questions like:

- What is your group like?

- What is this group’s history and where is it going?

- What are common concerns?

- Who are the people who get things done in this group? What are their phone numbers?

- How could the newspaper better fit into this community?

Team members met periodically to discuss what they had learned and to find common threads in what people were saying.

Then the teams moved on to the next level: A batch of interviews with the behind-the-scenes people whom the civic leaders had told us about. These folks know a lot of people in the community, help get things done and share information. They included a dentist who organized the annual haunted house, a homeowner’s association board member, veteran youth referees and coaches.

Again, interviews were not goal-oriented or tied to stories. Instead, sources filled the time with what they thought was important. Team members listened.

Those interviewed were asked where people in their group tended to gather, both formally and informally.

In the final phase of our mapping, team members visited these locations, sometimes called “third places,” including a popular ice cream parlor, a pizza place, a private lake and some community meetings. In these situations, team members observed the community dynamic in action, often without notebook in hand.

Teams talked and gelled the information from all of the interviews and observations to reach a consensus about what defined the group and who was in the know.

Then, we put our maps together into two-page documents that included:

- A description of each community.

- A list of community concerns and interests.

- Locations of hangouts or places where people gather.

- Names and phone numbers of active and involved citizens in each community.

We posted the maps on our Intranet site to make them available to the newspaper’s entire staff.

The Results

It was immediately obvious to team members that even if civic mapping were a complete flop, we would at least get a few good stories out of it. We just had no idea how many.

Some of the teams began keeping lists; others began working on the stories before the maps were completed.

Some examples: A 6-year-old soccer player with no arms; a teen hangout where an informal car show happens every Tuesday; people who only lived in Moreno Valley on weekends; an entire family of youth sports referees.

Civic mapping seemed to prove its point best in a routine story.

We’ve all done this one: Residents upset over a planned development.

Civic mapping helped us latch onto this controversial issue before it reached the planning commission. It got us so deep in sources that even the insiders were calling us to ask for the latest developments.

The situation progressed to standing-room-only City Council meetings, an early morning Council vote and, ultimately, lawsuits against the city.

The effects of civic mapping:

- Each story provided a variety of voices on each side rather than a

single mouthpiece speaking for the whole group. - Stories were laced with explanations of how the news related to the community’s vision of itself – its past and future aspirations.

- The reporter explored the benefits and consequences of various alternatives well before decisions were made.

- When breaking news occurred in the form of a lawsuit, inside lines to key sources produced a well-reported, relevant story in less than two hours.

This series of stories earned trust with our readers and sources. We were in on-the-porch conversations and we had earned our way there by giving them information about an issue that they had decided was “newsworthy.”

It all seems simple, but many hadn’t seen us on that porch for a long time.

The Hard Sell

We pay reporters to be critical, and they do their job. When something like civic mapping comes along, they sense a fad, more work and another fizzled initiative.

Many thought it would take hours and hours away from daily responsibilities for something intangible. It turned out that an hour or two of civic mapping each week didn’t dent the schedules as much as some expected.

Instead, some team members found freedom when managers gave priority to chats with sources without the burden of turning around stories.

“I had some skepticism,” said veteran Press-Enterprise reporter Marlowe Churchill. “But from a reporter’s standpoint, it was fun to pick people’s brains and not need to worry about a daily story at the end of the interview. By the time our committee was finished, we had an impressive list of story ideas.”

Our newspaper has decided to press on with civic mapping. Yes, for the stories, the competitive advantage and the richer contact lists.

But as the idea spreads from bureau to bureau, we hope something more will come of our journey. We’re looking for a change in mindset among our ranks. A story told from the vantage points of community members has a completely different flavor in focus and topic than those devised in the newsroom or by bureaucrats.

The copy smells authentic. And that’s because it is.