Winter 1995

Out of the Pressbox, onto the Field

By Edward M. Fouhy

Executive Director

Pew Center for Civic Journalism

After a year’s work and more than 40 trips around the country, it has become apparent that civic journalism is no longer a fragile seedling struggling to stay alive. It has become a topic of conversation among both journalists and community activists, the phrase has begun to show up in newspaper and magazine articles, and scores of enterprising projects are on the drawing boards for the coming year. It is tempting to think it is close to achieving the critical mass that is essential if it is to become self-sustaining. But like all new ideas, it must be nurtured, which is one purpose of this newsletter.

In our travels we have met many thoughtful editors and news directors who are willing to consider new ideas because of their uneasy sense of growing disconnection from their readers and viewers. Many are also worried about the enormous changes in the news business, which they see coming at them with the speed and force of a runaway locomotive; it is a technological revolution in communications that the Nieman Foundation’s Bill Kovach has called “the most profound change since Gutenberg moved knowledge from the pulpit to the hearth.” Some senior journalists are concerned about the alienation citizens seem to feel and the corrosive cynicism that affects politics at all levels. They observe the deterioration of robust public debate and the withdrawal of many citizens into narrow personal concerns at the expense of the public interest.

They are putting the traditional rivalry between newspapers and broadcasters behind them as they search for new ways to connect with their restless readers and the viewing public. They are doing what Knight Ridder’s CEO Jim Batten once described as, “coming down out of the press box and getting on the field, not as players but as referees.”

They are putting the traditional rivalry between newspapers and broadcasters behind them as they search for new ways to connect with their restless readers and the viewing public. They are doing what Knight Ridder’s CEO Jim Batten once described as, “coming down out of the press box and getting on the field, not as players but as referees.”

What is it they are looking to at a time of crisis and change? What is civic journalism? It is an idea, a work in progress, a growing conviction that journalism is, as Wichita Eagle editor Davis “Buzz” Merritt puts it, at the heart of public life and that a society with no public life has little need for journalism in any form. It is an effort to reconnect with readers and viewers who have been convinced they no longer matter, that their opinions are not important, that their leaders do not listen to them.

Justice Louis Brandeis liked to say, “The highest ranking office in a democracy is the office of citizen.” Civic journalism is an effort to restore the dignity and importance of that office, to regain journalism’s rightful role as the central source of the information free people need to debate, deliberate and finally to decide the questions they confront in a self-governing society.

It goes by many names — some call it community-connectedness journalism others, public journalism. The name doesn’t matter. What does matter is that some news executives — whether driven by altruism or the conviction that in the long run, purely market-driven journalism carries the seeds of its own destruction — have decided it may be one way to reconnect with a disconnected public and to secure the journalist’s central role in the public dialogue that characterizes democracy.

Batten and his newspapers, notably the Charlotte Observer and the Wichita Eagle, have pioneered this effort not only by doing vigorous reporting and analysis, but also by making strenuous efforts to identify and connect with the issues that are on their readers’ minds, and, when the need has been established, by becoming a catalyst for the civic life of their communities. The concept of civic journalism has now spread widely. Scores of journalists have attended seminars and weekend retreats, sponsored by the Radio and Television News Directors Foundation and the American Press Institute, where these ideas have been discussed and refined.

Editors and news directors have taken the message back to such cities as:

- Madison, Wisc., where Wisconsin public radio and television formed a partnership with The Wisconsin State Journal , CBS affiliate WISC-TV, and WHA-TV, the public station. The experiment here is nearly three years old and is flourishing.e Boston, where The Boston Globe joined NBC affiliate WBZ-TV and National Public Radio station WBUR in an election year alliance.

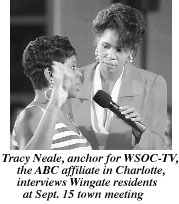

- Charlotte, N.C., where The Observer, WSOC-TV, and the Cox-owned ABC affiliate, have been joined by radio stations WPEG and WBAV to explore the impact of crime on citizens and to seek solutions after a painstaking block-by-block examination of the problem.

- San Francisco, where the partnership includes public station KQED, the San Francisco Chronicle, KRON-TV (the NBC affiliate) and its 24 hour all-news local cable channel.

Dallas, Seattle, Wichita, and Tallahassee are other cities where partnerships assisted by the Pew Center have come together around the concept of civic journalism. Many other newspapers and broadcast stations, instructed or inspired by these successful partnerships, have launched their own independent experiments.

Some election year partnerships have had what appears to be a deep and lasting impact. Sam Fleming of Boston’s WBUR and Amy McCombs, president of San Francisco’s Chronicle Broadcasting, say they have been so pleased with the results of their election year experiments they are determined to bring the same citizen orientation to every-day news coverage as they brought to their campaign coverage.

The role of the Pew Center has been to provide funding in cases where newsroom budgets are strained and where a modest contribution has been enough to smooth the way for a civic journalism project and media coalition.

For some editors and news directors these kinds of projects have been an antidote to a rising chorus of criticism of purely market-driven journalism from some of those who know the news business best. Carl Bernstein, of Watergate fame, startled a publishers meeting recently by describing the press as “in unusual trouble and in danger of losing its way. Increasingly, the picture of our societies as rendered in our media is illusionary, disfigured, unreal, out of touch with truth, disconnected from the true context of our life.” Quoted in Editor and Publisher, Bernstein declared “the misuse and abuse of free expression actually disempowers people by making them more cynical about public life.”

Peter Kann, chairman and CEO of the Dow Jones Co. and publisher of The Wall Street Journal, identified 10 disturbing trends in American journalism. Leading his list was the blurring of lines between news and entertainment and between news and opinion; the pessimism of so much current journalism; and what he seemed to regard as an assault on objectivity, “fashionable new philosophies that argue there are no basic values of right and wrong, that news is merely a matter of views, that truth is only in the eye of the beholder.” That is “a dangerous philosophy for any society, and a dagger at the heart of genuine journalism.”

Technological change is the other factor leading some to question the traditional ways of delivering news. While the information superhighway may be a boon to the availability and distribution of news, it can also be another way of driving people apart into tiny audience slivers, unable to come together for debate, discussion and decision on the vital public issues facing their community. What we are finding in our travels and conversations in newsrooms all over the country is a reaffirmation that journalism cannot be solely a business. The public interest must be the driving force behind all journalism. Without it, news becomes a minor form of entertainment with little claim to First Amendment protection.

Perhaps Kovach put it best: “Values for journalists are like stars to sailors — we may not be able to touch them but we are lost without them.”

They are putting the traditional rivalry between newspapers and broadcasters behind them as they search for new ways to connect with their restless readers and the viewing public. They are doing what Knight Ridder’s CEO Jim Batten once described as, “coming down out of the press box and getting on the field, not as players but as referees.”

They are putting the traditional rivalry between newspapers and broadcasters behind them as they search for new ways to connect with their restless readers and the viewing public. They are doing what Knight Ridder’s CEO Jim Batten once described as, “coming down out of the press box and getting on the field, not as players but as referees.”